As I exited the room of my father, Bill Inman at the nursing home yesterday, I wondered what life was all about.

To see a once-sturdy and tall man who was known in his younger days by neighbours and friends as a bloke who could fix anything from cars to washing machines, now reduced to a shell of his former self, barely able to lift his frail skin and bone from the wheelchair to the armchair, is a sad reminder that our dotage will not necessarily be kind to us.

At eighty-nine years of age, Dad is amazingly still a survivor. Having left home at fifteen to escape the on-again off-again bickering of his parents, he joined the Royal Air Force as an apprentice fitter.

At nineteen, he met and fell in love with my mother, whom he quickly married after a whirlwind romance.

Marriage was the done thing in those days. The advent of world war for a second time had exacerbated the need for people to grab at the chance of happiness, knowing that it might well be an all too short window of opportunity.

Having barely become acquainted, the couple were parted by the exploits of a certain anti-social socialist, called Adolf Hitler.

So, our young RAF engineer was off to war and at nineteen, he found himself under a barrage of bombs that rained down for twenty-three hours of the day on the Mediterranean island of Malta.

The convoys that carried life-sustaining supplies to the isolated fortress were mostly sunk en route by bomber planes and U-boats. Residents and servicemen alike were starving as the island’s resources dwindled.

My father tells stories of cracking open the biscuits on the table and allowing the weevils to crawl out so they could eat what was left.

My siblings and I thus suffered the childhood conditioning of having to eat every morsel that was on our dinner plates, because, “We were starving on Malta, you know”.

One day, my Dad, now a young Flight Sergeant, was walking along the site of the airstrip and stopped to talk with a chap doing repairs up a telegraph pole, when a bomb landed right where he would have been, had he not paused to chat.

On another occasion, when the workload of trying to repair fighter aircraft as fast as they were being damaged, led to a need for the engineers to work twelve hour rotational shifts, a bomb landed on the Sergeant’s barracks and destroyed, among other things, the bed on which he would have been sleeping, had he been off duty.

The barrage was incessant and the casualties among young friends were horrific, yet the herculean efforts of my father and his peers in holding the fort against overwhelming odds were incredible. The ‘Siege of Malta’ was later recognised as a major contributor to the victory in the North African war theatre and the eventual triumph of the Allies. The island itself was awarded the George Cross for the courage and determination of the whole community.

My Dad and his mates kept the hurricanes and the spitfires going so they could defend the island and do their best to protect the supply convoys from the German bombers. Between 1940 and 1943, there were 3,340 air raids on the beleaguered island.

The toll on the health of the young men was merciless. My father survived polio and meningitis, in addition to near starvation, thanks to the dedication of the hospital staff in Malta.

When he was gravely ill and pronounced critically so, the air force decided that his wife needed to be informed of the seriousness of his condition.

The fellow who delivered the telegram to my mother’s house in Chester had a bit of a shock when she fainted in front of him. She had only read as far as, “We regret to inform you…” when the colour drained from her cheeks and she collapsed.

That same telegram is in my father’s chamber at the nursing home, framed as a reminder of how close he had come to becoming a statistic of the war effort. Other framed accolades include telegrams from the Queen and the Prime Minister of Australia, congratulating them on their diamond (6oth) wedding anniversary, almost ten years ago.

My mother, Vera is 92 and still lives in the retirement village that is fortunately about a two minute walk from the nursing home. It is only my Dad’s illness that has separated the pair, who had raised a large family and run tourism businesses together in Jersey, while he also worked as an Engineering Supervisor for British Airways. He had a fall during the night, while on holiday in Busselton about a year ago.

Collapsing head first into some furniture, the injuries were terrible. He suffered numerous facial fractures, appalling bruising and abrasions and apparently some nerve damage during the impact. Lying in a pool of blood and inhaling a fair bit of it did not aid his struggling lungs, which had already contracted partial emphysema. Dad had been a heavy smoker in his youth, apparently having started the bad habit in an attempt to minimise hunger pangs on Malta.

Prior to this incident, Dad had still been driving to do the shopping and banking, living an independent life with his wife. He had survived a previous fall two years earlier that could easily have seen off a person in their forties. With bleeding inside the skull, causing pressure on his brain, we had all thought he was a ‘goner’ then. Yet the habitual survivor had pulled through, to our disbelief.

This time though, when he was flown up to Perth by the Royal Flying Doctor Service, he was almost unrecognisable.

As I saw him lying unconscious with a neck brace, an oxygen mask and a face that was swollen like he had been battered by a gang armed with baseball bats down a dark alley, I feared the worst.

A year later, after many comings and goings from almost every hospital in Perth, he is now in the high care facility, drinking thickened liquids and falling asleep during conversations. (Perhaps we visitors simply are that boring!)

Mum told him he has to get well for their seventieth wedding anniversary in September. He replied that he didn’t think he would make it. We all doubt that he will, yet I wouldn’t bet against him.

In contrast, one of my nieces is due to give birth soon, and my own daughter, Kim is merely four weeks away from bringing my first grandson into the world. Thus continues the cycle of human existence – as one life reaches its twilight, new ones herald a new dawn, born into a totally different world.

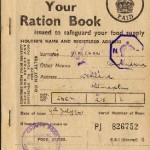

In Dad’s youth they had ration coupons, bombs falling around them, friends dying next to them, enforced separation from those they loved, hardship and struggle.

Today’s pampered generation are blissfully unaware of concepts like delayed gratification, sharing limited resources or putting the needs of others ahead of their own.

The other night, my girlfriend’s son, aged almost 18, complained bitterly that his Iphone 3 was ‘shit’ because it was playing up, with the inference that he was hard done by when his mother had gifted him her phone upgrade, because he should really have got the IPhone 4. I shook my head in disbelief, not just at this one spoilt adolescent, but at a generation who don’t quite ‘get it’. That’s probably as much our fault as theirs, because we had it so much easier than our parents did.

Maybe I didn’t quite ‘get it’ til I hit my milestone of turning fifty this year, but as I do my best to make small talk and cheer up my father, while he suffers the indignity of gradual bodily decline, I think that maybe I have begun to ‘get it’.

Now I realise how lucky I am, and how lucky we all are, to live in a free country, where we can voice our opinions; in a land of opportunity for those who are willing to work; in an environment of abundance; surrounded by a wealth of talent; free to enjoy our unlimited potential, constrained really only by those limitations we put on ourselves.

Men like my old Dad sacrificed some of the best years of their life to resist the shackles of tyrannical despotism, so that we could enjoy the best years of our lives in relative freedom. Luckily he’s had what some would call ‘a good innings’.

Forty-nine years ago, my father was spoon-feeding me my dinner as an infant. A week ago, in the hospital I was spoon-feeding an eighty-nine year old. We have come full circle.

From my perspective, I realise that we are indeed lucky. I live a fortunate life and I intend to live that life to the full. I will cross as many items from my personal ‘bucket list’ as I can.

For fourteen years I ran a backpackers hostel where I met over thirty-five thousand young people from all over the world. I was lucky enough to be able to help a lot of them in lots of ways. I now plan to continue helping others through business and life coaching, and through voluntary work, helping others to learn from my life’s experience of small victories as well as my setbacks and hopefully to overcome a few of the barriers to success.

As I prepare for the inevitable, some of my father’s many words resonate loudly in my memory, such as, “If a job’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well’.

Thanks Mum and Dad – I love you both and appreciate everything you have done for me over the years, though probably not enough.

I’m increasingly reminded of many things that I learned from my parents and hopefully I will have the chance to pass on a few pearls of wisdom to my children and grandchildren.

What will you choose to do with your opportunity?

Your future will be determined by the decisions and actions you take today. Your destiny is yours to shape. Make the most of the journey, because you never know how long it will be.

Until next time, count your blessings and remember to ‘seize the day’.

Well written Tony, good job. Cheers from Geoff and Sue